The History of Black Women Traveling The World

By Leroy Adams

Maya Angelou in New York

I am a student of Black Internationalism.

For the unfamiliar, the history of Black Internationalism is broadly defined as a global political, intellectual, and artistic movement of African-descended people engaged in a collective struggle to overthrow global white supremacy in its many forms.

In the 1940s, activists, scholars, and intellectuals engaged the ideas of black internationalism as an insurgent political culture emerging in response to slavery, colonialism, and white imperialism. The movement described the political and cultural ways Black communities collectively raised questions of struggle and liberation on a global scale and how Black people across the diaspora envisioned themselves beyond the boundaries of colonialism and European nation-states. And finally, to capture how people of African descent articulated global visions of freedom and forged transnational collaborations and solidarities with other people of color.

Even before the term became common parlance, numerous writers—W.E.B. Du Bois, Amy Jacques Garvey, Kwame Nkrumah, and Merze Tate, among them—engaged such ideas through various lenses, including Pan-Africanism, Garveyism, socialism, and Black Power.

In living our mission of celebrating, exploring, and connecting you to Black travel and culture globally, this Women's History Month, we're sharing the stories of Black women's transnational (and space exploration) movements throughout history.

Through international alliances, these women became powerful agents of change on global issues; through resilience and determination, they became international record-setters in sports and entertainment; and through a "phenomenal woman, that's me" attitude, they became history-makers in the galaxy.

Let's take a trip back in time to experience Black Internationalism through the travels and global contributions of some of history's most influential women.

POLITICAL & CULTURAL ACTIVIST

MAYA ANGELOU (Egypt and Ghana)

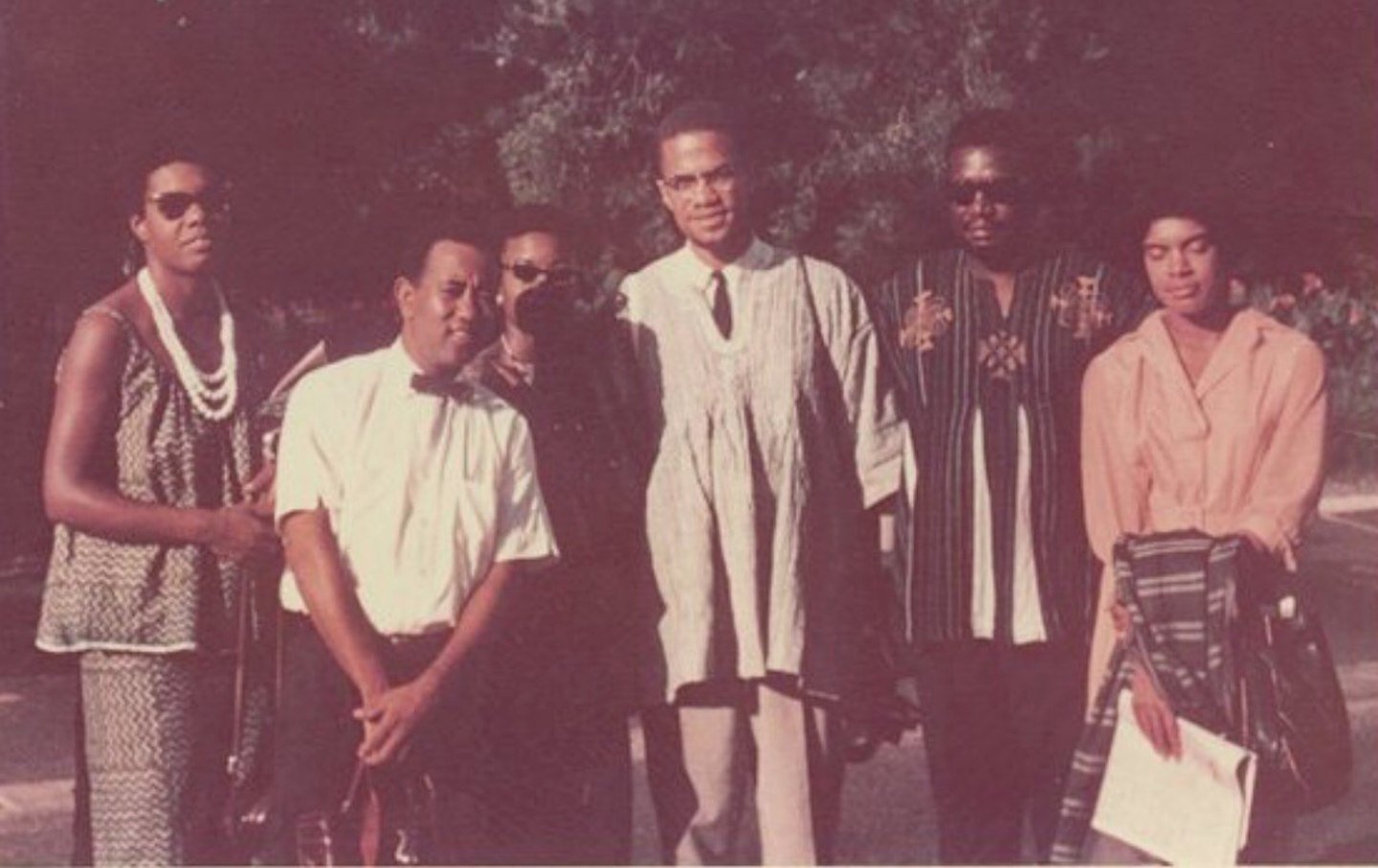

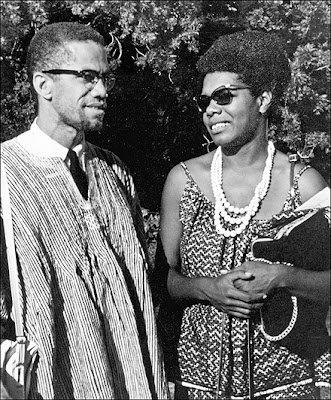

Maya Angelou (far left) with Malcolm X (third from the right) in Ghana.

“I encourage travel to as many destinations as possible for the sake of education as well as pleasure.”- Maya Angelou

EGYPT

In 1960, Maya Angelou moved to Cairo, Egypt. Historically, Egypt has provided a political space for Black Americans and Africans to envisage opportunities for mutual exchange and solidarity. In Egypt, Maya acquired a job as an editor for the Arab Observer - an English-language magazine. Angelou knew nothing about being a journalist, but David Du Bois - stepson to W.E.. Du Bois, a journalist in Cairo, introduced her to Zein Nagati, president of the Middle East Feature News Agency.

“Du Bois warned her that since she was neither Egyptian nor Arabic nor Moslem and since I would be the only woman working in the office, things would not be easy. He mentioned a salary that sounded like pots of gold to my ears…”

Du Bois would tell Maya, “Girl, you realize you and I are the only Black Americans working in the news media in the Middle East?”

Egypt’s influence is not lost on many Black Americans and is seen in the works of the late poet Maya Angelou. In her poem, “For Us, Who Dare Not Dare,” she articulated her desire to dream by writing:

Be me a Pharaoh

Build me high pyramids of stone and question

See me the Nile

at twilight

and jaguars moving to

the slow cool draught.

For Angelou, Egypt embodied the hopes and dreams of grandeur, not just because of its physical landscape but also the ability of its people to govern — especially given its 1952 independence from British military rule. Egypt occasionally featured as the backdrop to Angelou’s poems, as a trance coming to fruition. It was a living realm in which the African American poet collaborated with anti-colonial leaders from Ghana and South Africa.

On her arrival in 1960, Angelou’s descriptions of Cairo were visual and sonic. In one of her recollections, she exclaimed:

Street vendors held up their wares, beckoning to passersby. Young boys offered fresh fruit drinks, and on street corners, men stooped over food cooking on open grills. Scents of spices, manure, gasoline exhaust, flowers, and body sweat made the air in the car nearly visible. (The Heart of a Woman, Chapter 15)

GHANA

Maya Angelou and Malcolm X in Ghana.

In the 1960s, a group of African American artists and intellectuals moved to Ghana to attempt to redefine their relationship to citizenship in the U.S. and their African identities. Maya Angelou was part of this group.

In 1963, she settled in Ghana. There, Angelou became close to the Nkrumah regime, continuing her work as a journalist, broadcaster, and editor for a Pan-Africanist magazine. Drawing on her own experiences of racism in the U.S., her writing emphasized the connections between African and American activism, situating the struggle for civil rights within global campaigns against imperialism and discrimination.

They joined a small, tight-knit expatriate African American community, which included the great scholar and activist W. E. B. Du Bois, the writer William Gardner Smith, lawyer Pauli Murray, journalist Julian Mayfield, and sociologist St. Clair Drake. Angelou continued her work as a journalist and administrator at the University of Ghana. Her impression on her hosts was so strong that they honored her with a postal stamp.

CORRETA SCOTT KING (India, Switzerland, Jordan, Jerusalem)

Correta Scott King visits India.

"As we traveled through the land, we were greatly impressed by the part women played in the political life of India, far more than in our own country"

Traveling to forge alliances with foreign heads of state or studying another country's philosophical culture is not commonly associated with Coretta Scott King's legacy. Despite being behind her husband as he traveled the world, expanding his understanding of the global struggles of people of color and accepting Nobel Peace Prizes, her impact is often overlooked.

In 1957, Correta traveled to Ghana with her husband to attend the country's independence ceremony. Their visit was symbolic of a growing alliance of oppressed peoples and strategically well-timed. On the heels of the successful Montgomery Bus Boycott, their attendance represented an attempt to broaden the scope of the civil rights struggle in the United States.

For their honeymoon in 1958, Correta and Martin traveled to Mexico, where they observed first-hand the immense gap between extreme wealth and poverty.

In 1959, Mrs. King spent nearly a month in India on a pilgrimage to visit followers and sites associated with Mahatma Gandhi.

Corretta spoke at many of history's massive peace and justice rallies. In 1962, when she was in Switzerland with Dr. King—who was accepting the Nobel Peace Prize—she also served as the Women's Strike for Peace delegate to the 17-nation Disarmament Conference in Geneva.

In 1969, she was the first woman to preach in a statutory service at St. Paul's Cathedral in London.

She has also led goodwill missions to many African, Latin American, European, and Asia countries.

ANGELA DAVIS (Cuba, Soviet Union, Germany)

In 1965, Davis traveled to Germany to study at the ‘Institute of Social Research” for two years at the University of Berlin and then to the University of Paris for another year.

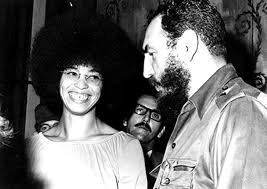

In 1969, Angela was received in Cuba by Fidel Castro as a member of a Communist Party Delegation.

Davis perceived Cuba as a “racism-free” country, which led her to say the following:

“Only under socialism could the fight against racism be successfully executed.”

After her acquittal in 1972, Angela Davis went on an international speaking tour, including visits to Cuba, the Soviet Union, and East Germany. During this tour, she earned honorary doctorates from Moscow State University in Russia, the University of Tashkent in Uzbekistan, and Karl Marx University in Leipzig, Germany.

Angela Davis speaks with Fidel Castro in Cuba.

SPORTS AND ENTERTAINMENT

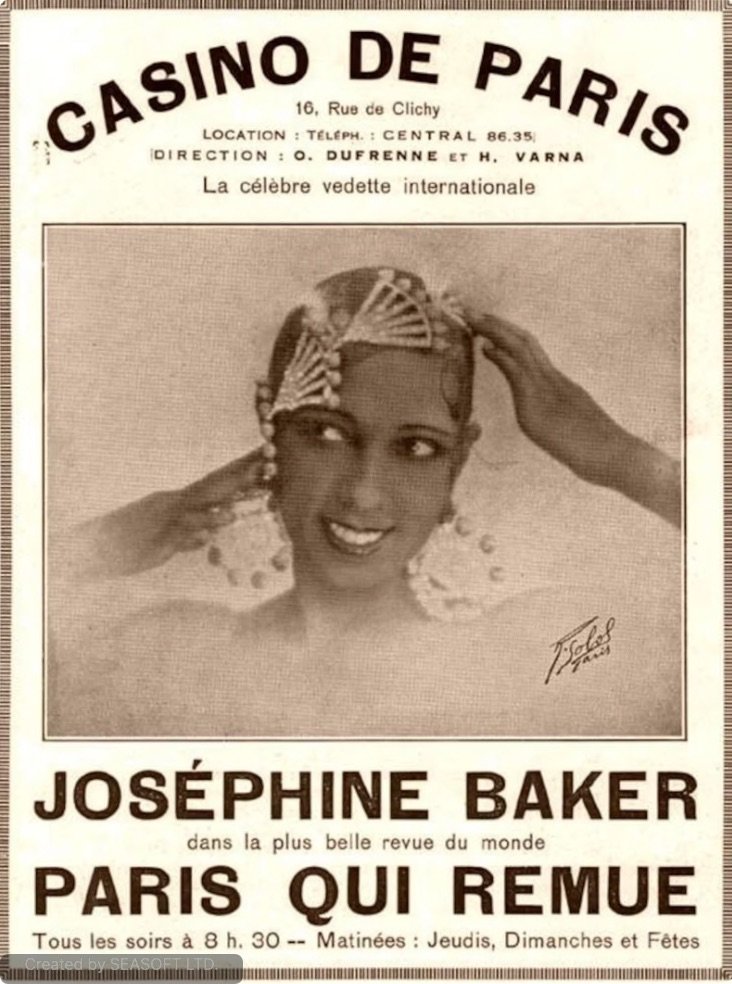

Jospehine Baker (France and Yugoslavia)

Josephine Baker in Yugoslavia

In her own words, Josephine Baker “was the girl who left St. Louis to come to Europe, to find freedom.”

In 1925, at the height of France’s obsession with American Jazz, Baker traveled to Paris to perform in La Revue Negre at the Theater des Champs-Elysees. In 1936, riding the wave of popularity she was enjoying in France, Baker returned to the United States to perform in the Ziegfeld Follies, hoping to establish herself as a performer in her own country. However, she was met with hostile, racist reactions and quickly returned to France, sad and disappointed at her mistreatment.

On moving to Europe, Josephine said,

“One day, I realized I was living in a country where I was afraid to be Black. It was only a country for white people. Not Black. So I left. I had been suffocating in the United States… A lot of us left, not because we wanted to leave, but because we couldn’t stand it anymore… I felt liberated in Paris.

Upon her return to France, Baker married French industrialist Jean Lion and obtained citizenship from the country that had embraced her as one of its own. When World War II erupted, Baker worked for the Red Cross during the occupation of France. As a member of the Free French forces, she entertained troops in Africa and the Middle East.

As a spy for the French Resistance, Baker would smuggle messages hidden in her sheet music and events in her underwear. Baker was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honour for these efforts with the rosette of Resistance, two of France’s highest military honors.

In 1929, Josephine Baker became the first Black American star to visit and perform in Yugoslavia.

Photo Credit: Dudely Edmundson

ALICE COACHMAN DAVIS (London Olympics)

Alice Coachman Davis at the 1948 London Olympics

Alice Coachman was the first Black woman from any country to win an Olympic gold medal.

In 1943, Coachman entered the Tuskegee Institute college division to study dressmaking while continuing to compete for the school’s track-and-field and basketball teams. As a member of the track-and-field team, she won four national championships for sprinting and high jumping.

People started pushing Coachman to try out for the Olympics. She was one of the best track-and-field competitors in the country, winning national titles in the 50m, 100m, and 400m relay.

The high jump was her event; from 1939 to 1948, she won the American national title annually. Yet, the Olympics were out of reach for many of those years. In 1940 and 1944, the games were canceled due to World War II. When the games were back in 1948, Coachman was still reluctant to try out for the team. She eventually attended the trials and destroyed the existing US high jump record while competing with a back injury.

On a rainy afternoon at Wembley Stadium in London in August 1948, Coachman competed for her Olympic gold in the high jump. She became the Gold Medalist when she cleared the 5 feet 6 1/8-inch bar on her first attempt, a new Olympic record. King George VI of Great Britain put the medal around her neck. With this medal, Coachman became the first Black woman to win Olympic gold and the only American woman to win a gold medal at the 1948 Olympic Games.

In 1952, Coachman became the first Black female athlete to endorse an international consumer brand, Coca-Cola.

EXPLORERS

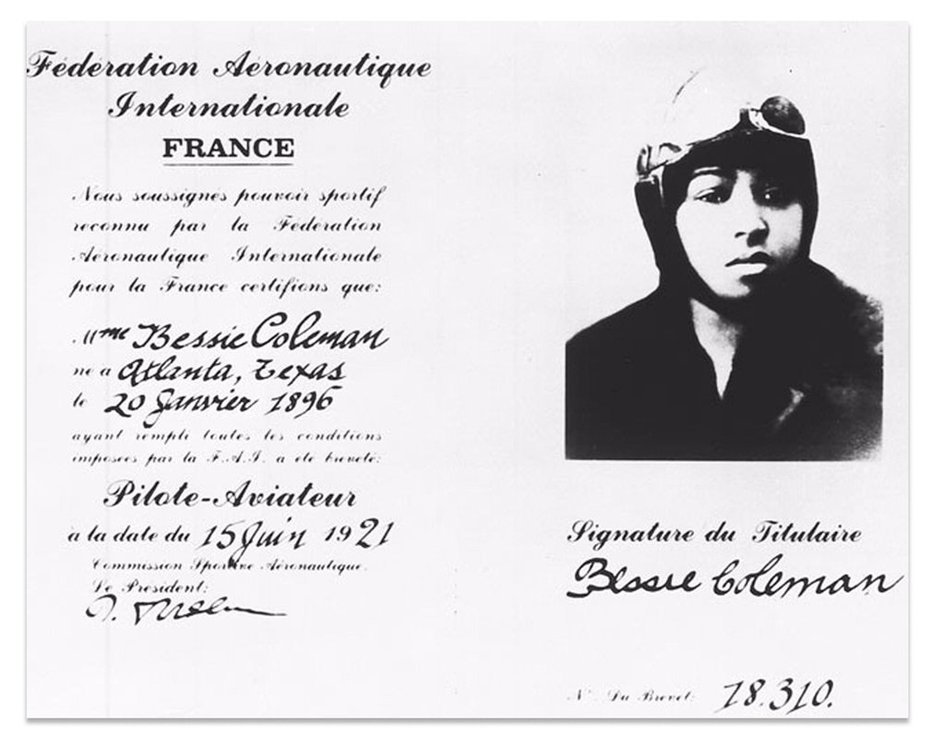

BESSIE COLEMAN

One of the men finds rest in puzzles.

Photo credit: Leroy Adams

Born in Atlanta, Texas, Bessie wanted to learn how to fly, but no US schools would teach her, so she went to France and got an international pilot's license.

Her brothers served in the military during World War I and came home with stories of their time in France. Her brother John teased her because French women were allowed to learn how to fly airplanes, and Coleman could not in the United States. Her brother's stories, along with other news of pilots in the war, inspired her to become a pilot. She applied to many flight schools across the country, but no school would take her because she was African American and a woman. Robert Abbot, a famous African American newspaper publisher, told her to move to France, where she could learn how to fly.

Her application to flight schools needed to be written in French, so she began taking French classes at night. Coleman was accepted at the Caudron Brothers' School of Aviation in Le Crotoy, France. She received her international pilot's license on June 15, 1921, from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale.

In 1922, she performed the first public flight by an African American woman.

She was famous for performing "loop-the-loops" and making the shape of an "8" in an airplane. People were fascinated by her performances, and she became more popular in the United States and Europe.

MAE JEMISON

Mae Jemison aboard the Endeavor

In 1992, Mae Jemison became the first Black woman to fly into space. She made 127 orbits around the Earth with six other astronauts on the space shuttle Endeavor. About her experience, she said:

“I sat there with a huge smile... I knew the girl from Chicago would go to space one day, but I did not foresee the smile she would have when it finally came to pass.”

After graduating from Stanford University in 1977, Jemison attended Cornell Medical School, where she earned her medical degree. While there, she went overseas to Thailand to work in a Cambodian refugee camp and led a study in Cuba. After graduating, she served as a medical officer and teacher of medical research in the Peace Corps for two years in Sierra Leone and Liberia.

She studied abroad in Cuba and Kenya. She also worked at a Cambodian refugee camp in Thailand.

A part of her, she said, has always been connected to Africa. At 26, she volunteered with the Peace Corps as a medical officer for Sierra Leone and Liberia, where she also taught and did medical research.

Mae Jemison in Kenya.