Shared Complexion Does Not Equate to Solidarity: The Challenges of Creating the ADSEN Network

By Leroy Adams

ADSEN Network Members gather in Baltimore

After the initial gathering of 100 people from sixty-four countries across the African Diaspora in Baltimore, our newly formed group—the African Diaspora Social Entrepreneurship Network (ADSEN)—faced a significant challenge.

SPAIN

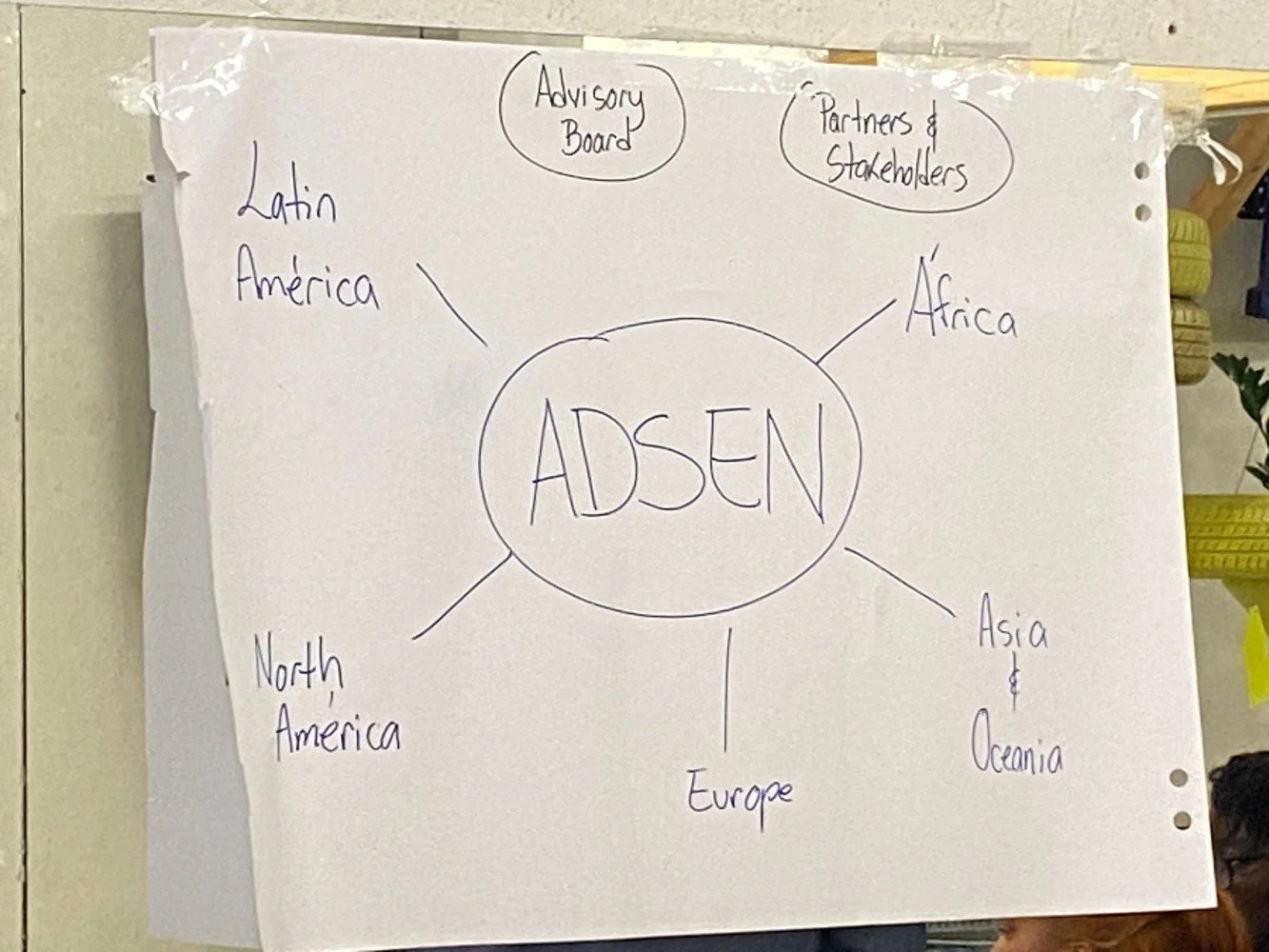

The U.S. State Department, which had organized our initial meeting, arranged a follow-up trip to Spain for 11 of us, selected from the larger group. The objective was clear: we were to develop the foundational elements of ADSEN—its vision, mission, and objectives, both short-term and long-term—and be prepared to present these back to the State Department. This would be the first real test to see if their vision for creating a global network to advise the Biden Administration on how to improve economic, political, and cultural relations with the African diaspora could work.

Delivering a presentation on the economics of Black travel to ADSEN members.

We would spend one week in Spain, a place not known for its Black history, but an experience that would significantly influence our time there. The first two days felt like a honeymoon. We arrived, soaking up the misty warmth of the Spanish air, and settled into a beautiful hotel that seemed to promise a week of productive and harmonious collaboration. The city itself was enchanting, with its narrow cobblestone streets, bustling plazas, and the ever-present aroma of freshly baked bread and rich coffee. We toured the city together, sharing laughter and excitement, marveling at the architecture, and enjoying the novelty of being in a new place. For those two days, it felt like we were on the same page, united in our purpose and eager to embark on this journey together.

But the honeymoon phase was short-lived. On the third day, the real work—and the real test—began.

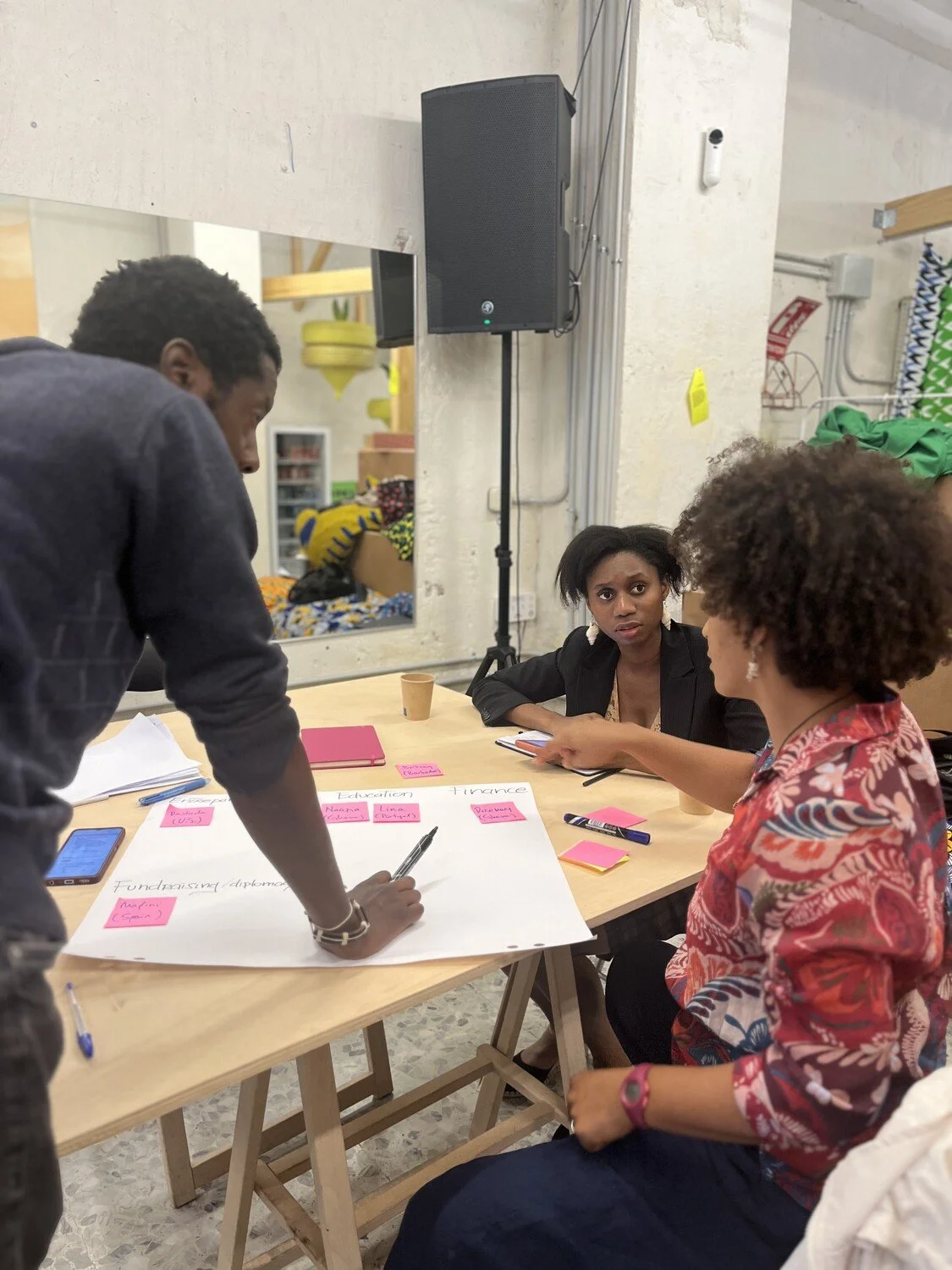

THE WORK BEGINS

Centro Cultural Espacio Afro

We gathered at Lo Afro Está En El Centro, a cultural center in the heart of Madrid that has become a meeting point for Black, African, and Afro-descendant culture in Spain. Our initial excitement was replaced with a palpable tension. It was time to get down to business, and the weight of our task settled over us like a thick fog. As we began to discuss the vision for ADSEN, the underlying tensions that had been momentarily masked by the beauty of our surroundings came bubbling to the surface. Differences in opinion, which had been suppressed by excitement and novelty in Baltimore, were now front and center.

The most pressing issue was how the network should be run. Who would be responsible for data tracking, story collection, fundraising, and governance? Whose work would be validated and recognized? What should the vision be for a group of 100 members of the African diaspora, each with their own unique perspective on what it meant to be part of this global community? How would we govern ourselves? Would the U.S. members, with their government funding the program, have more representatives or a more significant say in our decisions? And most importantly, what did we mean by "diaspora"? How would we ensure that this included not just people of African descent living outside the continent but also those who lived within Africa, who had expressed issues with the term during our time in Baltimore?

These questions were not easy to answer, and as the discussions grew more intense, it became clear that our upbringing, the politics we had been socialized into, and the cultures we had grown up in would outweigh any shared complexion or Pan-African identity. The differences between us—geographical, political, cultural—were stark and undeniable.

For instance, those of us from the United States had been raised in a country where race and identity were often framed through the lens of a binary struggle: Black versus White, oppressor versus oppressed. This perspective was deeply ingrained in how we approached issues of power structure and governance. On the other hand, members from African countries brought with them the complex dynamics of post-colonial societies, where power and wealth afforded Western countries a larger voice—and greater influence—in global politics. Then there were those from Europe and the Caribbean, who navigated different, yet equally complex, social and political landscapes, but often felt overlooked by the presence of Black Americans or Africans in these discussions on the diaspora.

ADSEN members meet with the founders of Africa 2.0

As the discussions continued, it became increasingly clear that our differences were not merely theoretical—they were deeply personal and rooted in our individual experiences. The debate over where we should focus our work first was perhaps the most contentious. For some, it was essential that the network focused on the experiences of African people. After all, the mandate from the White House was to improve relations with the African diaspora, starting with Africa. For others, it was perhaps more effective to focus our efforts on the diaspora, building a coalition of diverse voices and support that could bolster our efforts in Africa.

The conversation became more heated when we discussed governance. Should the U.S., as the primary funder, have more representatives or more power in decision-making? This question struck at the heart of the very issues we were trying to address: power dynamics, representation, and the fear of replicating systems of inequality within our own organization. It was a difficult conversation, but it was necessary.

Presenting a communications plan to ADSEN member

In that room, as the air thickened with tension, we quickly learned that solidarity could not be assumed simply because we shared the same complexion or a vague sense of Pan-African identity. Solidarity had to be built, brick by brick, through honest conversations, difficult compromises, and a willingness to confront the uncomfortable truths about our differences.

This experience proved the necessity of programs like ADSEN and the Black Atlantic Residency that bring together members of the African diaspora. It is not enough to simply declare a commitment to Pan-Africanism or diaspora unity. We need to be around each other, to engage in protocols, ideas, and thinking that challenge us to go beyond surface-level unity. We need to learn from each other, understand each other for who we truly are—beyond the color of our skin—and work together to build something that is genuinely inclusive and representative of the diverse experiences within the African diaspora.

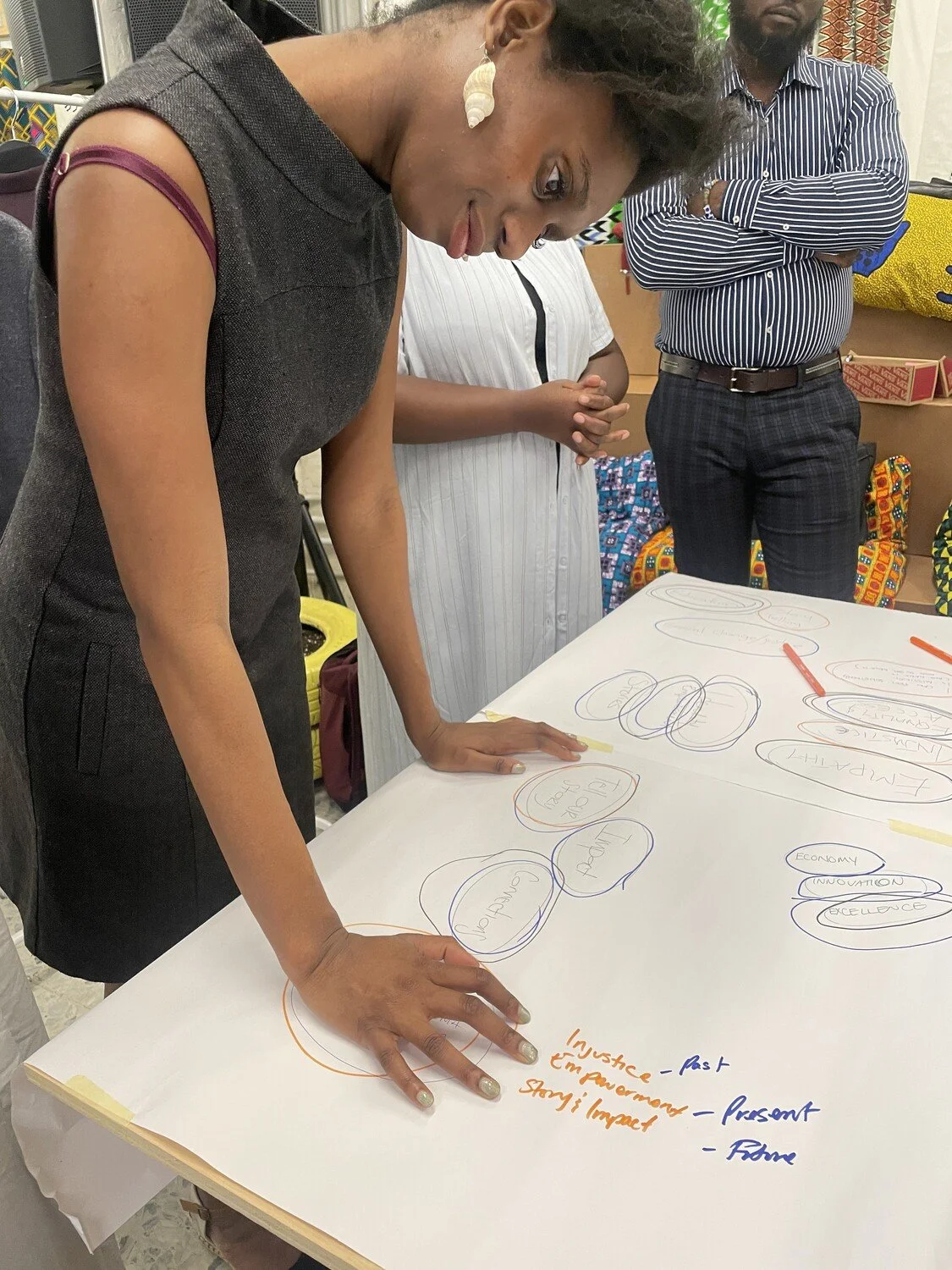

ADSEN member Grace (Australia) overlooks a team building activity.

A PATH FORWARD

As the week progressed, tension was replaced with dialogue and hope. By the end of our time in Madrid, we had crafted a mission statement that, while not perfect, reflected the input and perspectives of everyone in the room.

ADSEN Mission Statement

We are African Descendent Social Entrepreneurs (re)connecting with the continent by increasing the visibility of our socio-economic contributions and telling the stories of Africa and her Diaspora.

We had also established a set of objectives that would guide our work in the short term, with the understanding that these would evolve as the network grew and as we learned more about each other and the communities we were trying to serve.

But perhaps most importantly, we had proven to ourselves—and to each other—that despite our differences, we could work together. Our desire to build a network that would serve the diaspora far outweighed any individual agendas. The experience in Spain was a microcosm of the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead for ADSEN. It was a reminder that unity is not something that comes easily or naturally; it is something that must be worked for, nurtured, and protected.

ADSEN members present a governance plan.

As I reflect on that week in Spain, I am reminded of the words of Kwame Nkrumah: "We face neither East nor West; we face forward." The work we began in Spain was just the beginning of a long journey. It was our first real test, and while we did not emerge unscathed, we emerged stronger, with a clearer sense of purpose and a renewed commitment to the ideals of Pan-Africanism and diaspora unity.

We left Spain with more than just a set of documents to present to the U.S. State Department. We left with a deeper understanding of the complexities of our shared mission and the knowledge that if we are to succeed, we must continue to engage with each other—honestly, openly, and with a willingness to learn and grow.

One last picture before we depart to our corners of the world

In the end, the week in Spain was not just about creating a network; it was about laying the foundation for a new kind of diaspora unity, one that acknowledges and respects our differences while striving toward a common goal. It was a week that tested us, challenged us, and ultimately brought us closer to realizing the vision of a united African diaspora.